|

|

|

|

|

|

Judgement then does hold the notion of value

– and its negative; worthlessness.

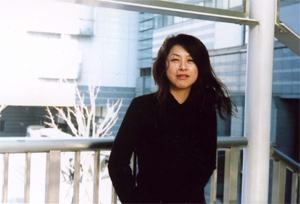

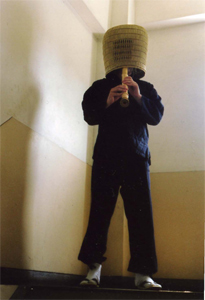

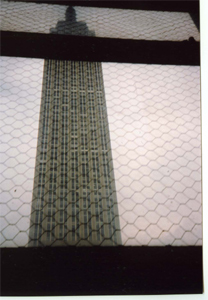

The images presented here are ostensive (that is in the way that “pink” is ostensive rather than factual), by this we mean that they suggest, that they show, or exhibit a degree of visual empathy rather than merely record factual or dramatic events; they do not render the “historic” moment. In this way the images are not allied to memory; there is no narrative structure; there are no anecdotes. Empathy – what does this mean? In art, generally, the mimicking of external reality. In German it is “einfuhlung” or “in feeling”, that is the power of projecting one’s personality into an object of contemplation, and in so doing, fully comprehending that object. |

|

|

Visual empathy, in the treatise “Abstraction and Empathy” by Wilhelm Worringer, first published in 1908, is juxtaposed with abstract imagination, that is non-figurative invention or a principle of order; a formal structure. The conclusion being that “all art is equally pervaded by abstract imagination and visual empathy” (Anna Meseure, 1991). |

|

|

This may be considered obsolete today however Hilton Kramer, in his introduction to “Abstraction and Empathy”, has argued otherwise. When viewing these photographs it is worth keeping in mind that while the images possess a degree of visual empathy, the relationship between the images tends toward the abstract; that is they are contiguous, there is a proximity of ideas or association of subjects that to a greater or lesser extent have some form of contact. They touch. “The need for organization is a need common to science and art … ‘taxonomy’ … has eminent aesthetic value”. (Levi-Strauss, 1976). |

|

|

And to quote Claude Levi-Strauss, from his ‘The Savage Mind’, more extensively; “The problem of art (is that) it lies half-way between scientific knowledge and mythical or magical thought. …The aesthetic emotion is the result of this union between the structural order and the order of events, which is brought about within a thing created by man and so also in effect by the observer who discovers the possibility of such a union through the work of art. |

|

|

“… In the case of works of art, the starting

point is a set of one or more objects and one or more events which aesthetic

creation unifies by revealing a common structure. Art thus proceeds from

a set (object + event) to the discovery of its structure.

Levi-Strauss also states, “Images cannot be ideas but they can play the part of signs…”, that is signs are an intermediary between images and concepts. “Images are fixed, linked in a single way to the mental act which accompanies them.” And so the photograph, or a photograph, can present a singular difficulty: is it an image or a sign? Space limitations prevent me from going further into this, however, it is a problem to keep in mind. |

|

|

|

The act of ordering, of organizing, therefore producing a rudimentary form of classification, of a group of photographs, whether serially or through permutations or any other system does attempt to resolve this issue (“classificatory systems as systems of meaning”). But let us consider what a photograph essentially does; it isolates a subject. Something that one’s sight may merely graze, something that appears at the edge of vision, may grasp the attention – or be grasped by one’s attention. The photograph isolates the perception. The image is held and bracketed off from its immediate environment. Context is dissolved. (Here, I’m interested in juxtaposing “graze” with “gaze”; one merely touches while the other fixes.) |

|

|

When we consider the display or exhibiting of

photographic images we find these images connect to other subjects, to

other viewers; photography then becomes as much about sharing as it does

about isolating and holding individual objects. And the concern is with

“to graze” aligned with “to share” as opposed to “to fix” aligned with

“to captivate”. At this point I consider this to be so; although the eye

of the photographer may isolate and bracket the subject, that eye only

touches the subject in the most peripheral way. It touches and moves on.

Sharing occurs when the viewer’s eye(s) once again graze the photograph

– as object. The viewer is not transfixed. The moment of sharing is only

brief, but there is a connection. A relationship has been formed: subject?actor

(photographer)?object?viewer. A tenuous relationship but that is where

worth lies. It is this relationship which acts as the force – and legitimacy—of

consecration: that is “all things are (being) equal”.

|

|

|

For the artist it must be the private aesthetic

sense – the pertinence of which can only be quantified by public interest

– which permits the actual act of consecration; “and all sacred things

must have their place” (Levi-Strauss). This once again appears as a paradoxical

statement, however it is this paradox that is at the very heart of artistic

activity. “Popular culture reflects consensus reality”, and that consensus

reality is fluid; whereas images are fixed, consensus reality is never

fixed.

Fundamentally though it is really about pleasure. The pleasure taken in an image rendered upon paper, in an image that produces a charge or a surge. This sensation is more properly a quality of consciousness; a quality that motivates and a quality that is in turn actualized, made real, and so joins us, or touches us with the greater, the lived world. References: Kramer, Hilton; Introduction to Abstraction and Empathy, Elephant Paperbacks, 1997. Levi-Strauss, Claude; The Savage Mind. Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1976. Meseure, Anna; Auguste Macke, Taschen, 1991. Worringer, Wilhelm; Abstraction and Empathy, Elephant Paperbacks, 1997. |

|

|

Additional Notes: “Logic consists in the establishment of

necessary connections”

Other?Aesthetic Strategies: Description (explanation); Contrast (opposites)?

transference (the sign is shifted from one subject to another); incongruity

(not in agreement); susceptibility (admitting of another interpretation);

comparison (similarity/ dissimilarity);

|

|

|

|